缅因州佩诺布斯科特县正在努力应对该州历史上最大规模的艾滋病毒疫情。该县是班戈市的所在地,该市拥有约 32,000 人,在近两年内发现了 28 例新病例。这是该时间长度的典型数字的七倍。几乎所有病例都是吸毒者和无家可归者。

公共卫生专家和当地倡导者表示,疫情是由多种实地因素共同推动的:向吸毒者分发无菌注射器的项目被搁置和关闭,专注于艾滋病毒的医疗服务提供者短缺,以及清理该市最大的无家可归者营地,这颠覆了对居住在那里的新确诊者的护理。

但这些问题可能不会长期存在。

特朗普政府正在全国范围内推行类似的策略。在最近的一项行政命令中,特朗普呼吁取消对减少危害的计划的资助——这是一个广义的术语,包括许多公共卫生干预措施,包括注射器服务,旨在让吸毒者活下去。这种努力有时会引起争议,批评者称它们助长了非法活动。该行政命令还支持迫使无家可归者离开街头接受治疗。此前,政府削减或推迟了对各种成瘾和艾滋病毒相关项目的资助,并掏空了专注于这些主题的联邦机构。

>>idth=”1504″ height=”2015″ />

>>idth=”1504″ height=”2015″ />The administration says its approach will increase public safety, but decades of research suggest otherwise. Many advocates and researchers warn these efforts could spark more outbreaks like the one in Bangor.

“That feels inevitable,” said Laura Pegram, director of Drug User Health for NASTAD, an association of public health officials who administer HIV and hepatitis progr

ams.She said people who use drugs face a trifecta of risks: HIV, hepatitis C, and overdose. “Across the country, I think we’ll start to see those three things starting to be on the rise again.”

“That will be incredibly costly,” she added — in dollars and “in a real human way.”

Outbreaks that start among people who use drugs can easily spread to those who don’t.

An HIV Outbreak

The first HIV case in Bangor’s current outbreak appeared in October 2023, well before Trump’s return to the presidency.</p>

Puthiery Va, director of Maine’s public health department, attributed the emergence to the opioid epidemic, housing shortages, and the greater Bangor area’s sparse health care serv

i

ces.Local advocates highlighted an additional, acute factor: supply shortages at the region’s largest syringe services program and its subsequent closure.

A nonprofit that provided health care and social services to people who use drugs, Health Equity Alliance, or HEAL, distributed more than half a million sterile needles ann

ua

lly.Like other such programs nationwide, its goal was to prevent the spread of infectious disease that can occur if people share needles to inject

dr ugs.However, financial struggles and mismanagement led to severe shortages in recent years. Former HEAL executive director Josh D’Alessio acknowledged such issues, telling KFF Health News, “We did run out of syringes” at times or limit how many participants could take. Several of these shortages struck in the fall of 2023, leading HEAL staffers to suggest a link to the first HIV case.

Research suggests a strong connection between past HIV outbreaks among people who use

drugs a nd lack of access to sterile needles, said Thomas Stopka, an epidemiologist at Tufts University School of Medicine.A 2015 outbreak in Scott County, Indiana, and one in the Merrimack Valley of Massachusetts a few years later were curbed only after syringe services programs ramped up</

a>, he s aid. If such programs had existed sooner in Scott County, more than a hundred infections could have been prevented, one study suggested</a>.Va, who leads the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, said she considers the shortage of syringe services in the Bangor area to be a factor in the outbreak but

not the primary ca use.Stopka said the best practice during an outbreak “is to amplify access to sterile syringes.”

But Trump’s recent executive order links harm-reduction programs to crime, saying such efforts “only facilitate illegal drug use and its attendant ha

rm.” The order doesn’t name syringe services programs — which have been supported by both Democrats and Republicans in the past — but it targets “safe consumption” sites, where people can use drugs under supervision. Many advocates worry the attacks will be broader.A letter from the nation’s leading addiction agency expanding on Trump’s executive order said federal funds cannot be used to bu

y syringes or drug pi pes. However, that has been true for most of the past few decades. The letter did not address supporting general operating costs for syringe services programs.Department of Health and Human Services spokesperson Andrew Nixon told KFF Health News that the administration is committed to “addressing the addiction and overdose crisis impacting commu

nities across our nati on.” But he and spokespeople for the White House did not respond to specific questions about the administration’s stance toward syringe services. <p>In Bangor, some locals have raised concerns about harm reduction that echo the president’s. At a March 2024 City Council meeting — shortly after a syringe services program was newly certified by the state to operate locally — residents and business owners said they felt unsafe with the growing population of people who were homeless and using drugs. They worried syringe programs were fueling the behavior. <p>But research suggests syringe services programs reduce discarded needles in the community and do not increase crime. They <a href=”https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5621373/”>can halve new HIV and hepatitis C cases, increase entry</a> into addiction treatment fivefold, and savetaxpayer money. They are also leading distributors of overdose reversal medications, the use of which many communities — and the Trump administration — have said they support.The city ultimately decided the newly certified program, Needlepoint Sanctuary, could not operate in prominent public parks or squares.

Maine certified Needlepoint Sanctuary to distribute sterile syringes to people who use drugs, but the group has encountered obstacles with the city, which does not want it operating in prominent public parks or squares. (Needlepoint Sanctuary)

Maine certified Needlepoint Sanctuary to distribute sterile syringes to people who use drugs, but the group has encountered obstacles with the city, which does not want it operating in prominent public parks or squares. (Needlepoint Sanctuary) Needlepoint Sanctuary regularly handed out food, clothing, and other supplies to people living at the largest homeless encampment in Bangor, Maine. (Needlepoint Sanctuary)

Needlepoint Sanctuary regularly handed out food, clothing, and other supplies to people living at the largest homeless encampment in Bangor, Maine. (Needlepoint Sanctuary)In the following months, Needlepoint ran its syringe services only at the city’s largest homeless encampment, where several people had tested positive for HIV, said the group’s executive director, William “Willie” Hurley. That ended in February when the city cleared the encampment.

This summer, Needlepoint secured a private location for its syringe services but shut it down five days later when city officials raised zoning concerns.

Jennifer Gunderman, director of Bangor’s health department, said the city is trying to strike a balance between “making services available and what the community wants.”

“Getting the buy-in of most of the community” is “critical to the future of harm reduction,” she said.

Other cities in Maine and beyond have seen backlash result in new laws that restrict how syringe services programs operate or shutter them.

Gunderman said she is hoping to avoid that in Bangor.

Clearing Encampments

Trump’s recent executive o

rder also calls for clearing homeless people off the street and involuntarily committing them to treatment facilities.The administration is enacting this policy in Washington, D.C., where it has bulldozed tents and threatened homeless people with fines and jail time if they don’t

leave he streets.White House spokesperson Abigail Jackson said people have the option to be tak

en to a shelter or receive addiction and mental health services.Similar policies have taken hold nationwide in recent years, even in liberal hubs like New York and California</a>.

Last year in Bangor, as a homeless encampment that had existed for several years grew to nearly 100 residents, business owners and locals called for its clearing.

Some advocates and social service providers warned that doing so could exacerbate the HIV outbreak and overdose crisis. At two City Council meetings in November, they explained that it would be difficult to find people they served after a clearing and that scattering newly diagnosed people <a href=”https://www.youtube.com/live/rkCl9rrPZ1s”>could spark HIV clusters elsewhere.

“Plenty of people said you’re going to lose track of these people,” Amy Clark, a board member for the Bangor Area Recovery Network, told KFF Health News. “They did it anyway.”

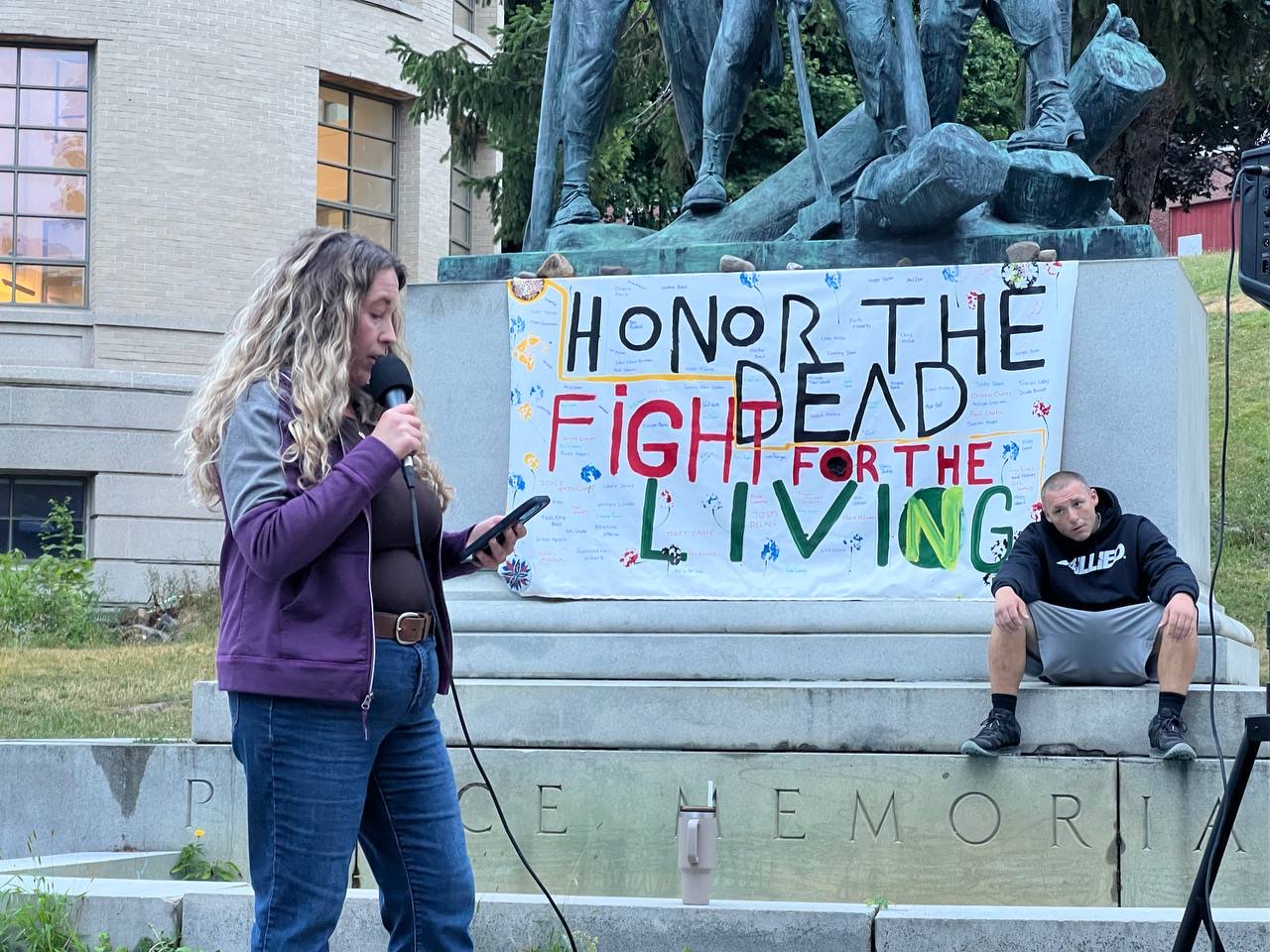

Amy Clark, a board member for the Bangor Area Recovery Network, speaks at an Overdose Awareness Rally outside Bangor City Hall in August 2025.(Ash Hebert)

Amy Clark, a board member for the Bangor Area Recovery Network, speaks at an Overdose Awareness Rally outside Bangor City Hall in August 2025.(Ash Hebert)‘I’m Still Alive’

Two months after clearing the encampment, the city reported not knowing the location of more than a third of the people who had lived there.

Clark said it’s not surprising that the city couldn’t connect everyone to housing or treatment. Many people distrust these services, shelters are frequently full, and treatment services are scarce. “Where exactly are these people supposed to go?” she said.

City officials stressed in Council meetings and reports that they were taking a humane approach. They ramped up social services for months leading up to the clearing, connecting people to everything from housing to storage facilities and laundry.

Gunderman, the city health director, said she knows the sweep wasn’t ideal but that neither was crowding folks in an unsanitary encampment. “It was a situation where there weren’t a lot of great answers,” she said.

To help track folks from the encampment and keep them engaged in HIV treatment, the city is now using about $550,000 in opioid settlement funds to hire two case managers. (The only other local HIV medical case management program shuttered over the summer.)

“What we know from outreach we’ve been doing already is that we spend a lot of time looking for people,” Gunderman said.

Jason, who has been homeless for most of the past decade and tested positive for HIV this year, has seen that in action.

Members of what he calls his medical team have scoured the streets for hours to find his tent and remind him to take his HIV treatment shots, he said. Some picked up prescriptions and delivered them to him.

“They’ve made sure I’m taken care of,” Jason said. (KFF Health News agreed to use only his first name to protect his privacy.)

Jason believes he got the virus last year at the homeless encampment while using drugs that someone else prepared. He had tried to avoid the encampment for months. But whenever he set up his tent elsewhere, he said, police officers told him to move.

When he got the diagnosis, he thought of his uncle, who died of AIDS in the 1980s.

“It hurts to talk about,” Jason said, “but I’m still alive.”

After months of treatment, his viral load is now undetectable. Over the summer, his team helped him find housing.

But Jason is still struggling to find sterile needles regularly. He worries about others facing a shortage.

“That’s how this outbreak has been spreading more and more,” Jason said. “Every time we turn around there’s another case.”

</figure>